Working with Jupyter notebooks#

Jupyter notebooks are ubiquitous in the fields of data analysis, data science, and education. There are a number of reasons for their popularity, some of which are (in no particular order):

They are user-friendly.

They allow for richer outputs than plain code (e.g, images, equations, HTML, and prose).

They allow for interactive, human-in-the-loop computing.

They provide an easy route to publishing papers, technical documents, and blog posts that involve computation.

They can be served over the internet, and can live in the cloud.

However, the popularity of the format has also revealed some of its drawbacks, and prompted criticism of how notebooks are used. In particular, version control and reproducibility remain major problems for notebook users. For a cogent and entertaining summary of some of these criticisms, see this talk from Joel Grus.

This document is meant to outline some recommendations for how to best use notebooks.

Notebooks and Reproducibility#

Scientific software has a problem with reproducibility.

Notebooks, in particular, introduce some extra problems for reproducibility. Because they are highly dynamic, interactive documents, they encourage out-of-order execution, re-executing cells many times, and frequent kernel restarts. This is often useful. You can tweak the results of a plot without rerunning an expensive analysis. You can load data once in an introductory cell, then perform a number of exploratory analyses without having to reload it every time.

However, this execution style commonly ends with results that are not reproducible. Another analyst running the same notebook will come up with a completely different result, or the notebook may not even run.

For these reasons, it is a good idea to make sure that a notebook runs from start to finish without any intervention. This should be a habit for everyone before committing changes to a notebook.

It may also be useful to parameterize execution of a notebook using a tool like papermill. This will allow you to run notebooks via a command line. This can be driven via automation tools like Makefiles, and can keep us honest about exactly how reproducible our analyses are: if a notebook analysis cannot be run without human intervention, it is not reproducible.

This all can be summarized as “restart and run all, or it didn’t happen.”

Notebooks and Version Control#

Jupyter notebooks are stored as JSON documents. While this is a rich format for storing things like metadata and code outputs, it is not particularly human readable. This makes diffs to notebooks difficult to read, and using them with most version control tools is painful.

There are a few things that can be done to mitigate this:

Don’t commit changes to a notebook unless you intend to. Often opening and running a notebook can result in different metadata, slightly different results, or produce errors. In general, these differences are not worth committing to a code repository, and such commits will mostly read as noise in your version history.

Use a tool like

nbdime. This provides command-line tools for diffing and merging notebooks. It provides git integration and a small web app for viewing differences between notebooks. It is also available as a JupyterLab extension.Move some code into scripts. There will often be large code blocks in notebooks. Sometimes these code blocks are duplicated among many notebooks within a project repository. Examples include code for cleaning and preprocessing data. Often such code is best removed from the interactive notebook environment and put in plain-text scripts, where it can be more easily automated and tracked.

Prose and Documentation#

One of the best features about notebooks is that they allow for richer content than normal scripts. In addition to code comments, they allow for images, equations, and markdown cells. You should use those!

Markdown cells allow for especially good documentation of what a notebook is doing. They allow for nested headings, lists, links, and references. Such documentation can make a huge difference when sharing notebooks within and between teams.

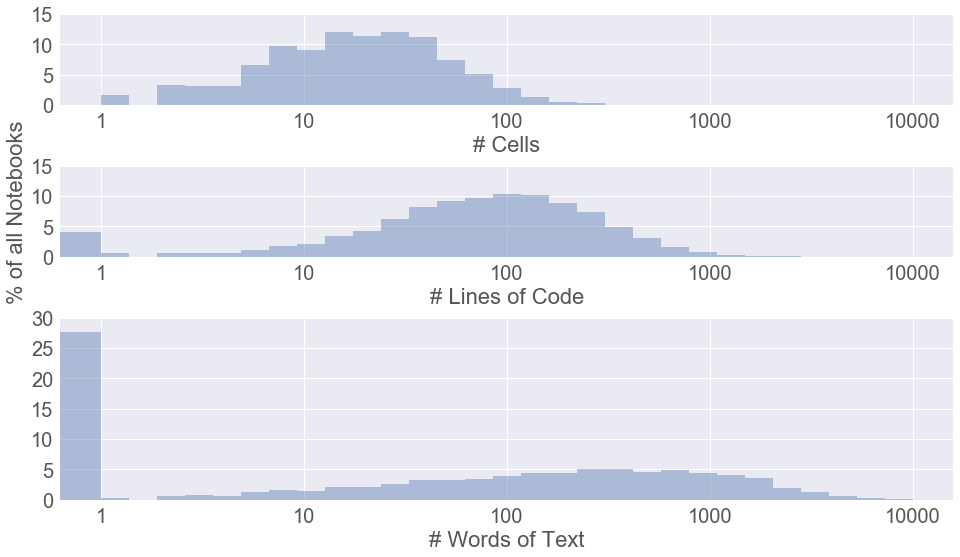

Adam Rule performed a study of all the Jupyter notebooks publicly available on GitHub.

One of the most remarkable findings of this study was just how many notebooks include no markdown cells at all, as seen in the third panel:

Over a quarter of notebooks include no prose. We should endeavor to not be in that first bin.

Data Access#

Many attempts to reproduce data analyses fail quickly.

This is because the original analyst referred to datasets that are not accessible to others. This may be because it relied on a file that doesn’t exist on other systems, or because they hard-coded a file path specific to their laptop’s file system, or because it relied on login credentials that others do not use.

These problems are not specific to notebooks, but often arise in a notebook environment. A few strategies to mitigate these issues:

Small datasets (less than a few megabytes) may be included in the code repositories for analyses.

Larger datasets may be stored elsewhere (S3, GCS, data portals, databases). However, instructions to access them should be given in the repository. Tools like intake can help here.

Credentials to access private data sources should be read from environment variables, and never stored in code repositories or saved to notebooks. The environment variables needed to access the data for an analysis should be documented in the project

README.